Mostowy, Jason, et al. “Early life ecology of the invasive lionfish (Pterois spp.) in the western Atlantic.” Plos one 15.12 (2020): e0243138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243138

King of the Reef

Lionfish are native to the Indo-Pacific region, but in 1985, they were introduced to the Atlantic. Several sources blame the aquarium trade and people who owned them as pets with releasing the lionfish and allowing them to become established in non-native bodies of water. Now classified as an invasive species, they are destroying reef ecosystems and food webs across the Western Atlantic. The Caribbean has been particularly hard-hit, as adult lionfish have almost no natural predators in this region and eat many fish of economic value (like snapper or grouper). Lionfish also reproduce quickly, making it extremely difficult to keep their population under control. Organizations in Florida sometimes offer bounties for them, and many countries encourage snorkelers or divers to cull them via spearfishing. Over the past several years, locals have incorporated lionfish meat into their meals, providing an extra economic incentive for spearfishing. However, lionfish have poisonous spines, so harvesting them can be somewhat dangerous without proper training.

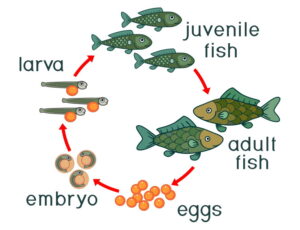

Lionfish Life Cycles

Unlike most other reef-fish, lionfish can reproduce rapidly throughout the year. In fact, one article reports that some lionfish are capable of laying about 42,000 eggs once every three days! While there have been numerous papers about lionfish breeding and habits once they become adults, not much is known about the survival and growth rates of baby lionfish, also known as lionfish larvae. Since many marine fish larvae have a low survival rate, Mostowy and his colleagues decided to survey the Gulf of Mexico to learn about lionfish larvae in hopes that the results could provide insight on how to control the population.

The Survey:

In order to better understand the larval stage of the lionfish life cycle, the authors surveyed over 1,800 sites in 16 regions throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean from 2009 to 2016 (figure 2).

In each of these regions, the team identified:

-

The depth at which lionfish larvae were most commonly found

-

Environmental variables such as temperature, salinity, currents and phytoplankton concentration

-

Size and probable age of the lionfish larvae

The data were compiled, and, through several calculations, the spatial distribution and density of lionfish was overlain on a map of the entire region, giving a comprehensive overview of lionfish presence in the Western Atlantic. That’s not all the team was able to do with the data, though. They were also able to build detailed models for the probability of lionfish presence in each region and the times at which they were most likely to spawn throughout the year.

The Results:

The authors came up with five main findings from their surveys and models.

-

Lionfish larvae were present at ~8% of the sites sampled.

-

The growth rate of lionfish larvae was much faster than other reef fish, meaning that they mature faster and spend less time vulnerable to predation.

-

Lionfish (and other reef fish) are more likely to spawn in the days leading up to a full moon in what’s known as a synchronous spawning event. Corals do this too!

-

The number of lionfish larvae likely correspond to the order in which the lionfish invaded Gulf of Mexico.

-

High densities of adult lionfish can actually decrease the size and amount of larvae they produce.

Future Directions:

Together, these findings provide valuable insight to the life cycle of the lionfish and the authors highlight some ways to manage the population of lionfish. The authors recommend more research on lionfish larvae, but the results hint that the larvae may be just as adaptable as their adult counterparts. They also mention that warmer water temperature could increase larvae survival rates and they stress the importance of monitoring how climate change could increase the geographic range of lionfish. This doesn’t bode well for the reef ecosystems of the Caribbean or the rest of the Western Atlantic. However, creating more models like the ones above may help to target the places that need the most attention or immediate response in population control.

I recently graduated with a degree in Environmental Earth Science and Sustainability from Miami University of Ohio, and I recently started my MSc at the University of Victoria. While my undergraduate research focused on biogeochemical cycles in lakes and streams, I am excited to pursue my MSc in the El-Sabaawi Lab and explore how urbanization might impact fisheries. In my free time, I love to travel to somewhere off the beaten path, read fantasy novels, try new recipes, and plan my next trip to the ocean.