Reviewing: Gary, S. F., Fox, A. D., Biastoch, A., Roberts, J. M. & Cunningham, S. A. Larval behaviour, dispersal and population connectivity in the deep sea. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67503-7

Critical Connections

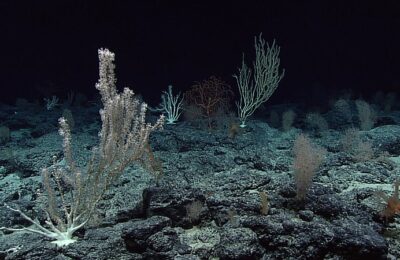

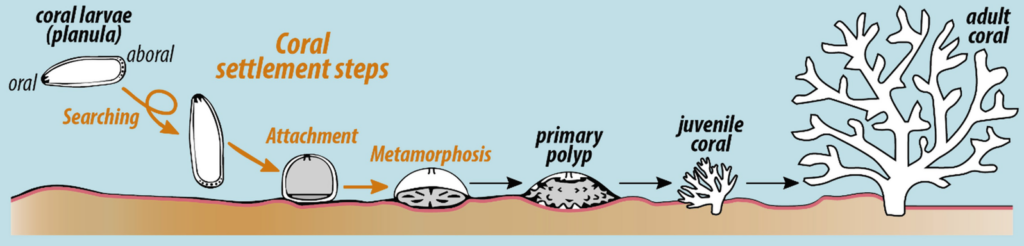

Benthic animals are those who spend most, if not all, of their adult life on the seafloor, e.g., corals, barnacles, sea stars. Because they are either very slow or permanently stuck to the seafloor, they utilize dispersing offspring, or larvae, to reproduce. The larvae are tiny relative to the size of the adult, which enables them to get carried over large distances with the currents before maturing and settling on the seafloor. To see some great footage of larvae in action, check out the Instagram tag “marine larvae”.

Large areas of pristine marine ecosystems have become fragmented due to human impact into a mosaic of natural and altered habitats. Because few animals have adapted to the resulting barriers in their migration, foraging, and mating, many species are experiencing declining populations and even extinction. Species can be sustained by the network of individuals across the ecosystem and how much they interaction, or what ecologists refer to as a species’ connectivity.

Larvae are critical for the connectivity of marine species because they are able to disperse and find new habitat, mix with other populations to promote resilience and recolonize impacted areas. Larvae utilize a variety of strategies to maximize their survival and determine where they get dispersed. Some have lots of fat to make them extra buoyant; some have long larval durations to maximize the area they get spread over; some use vertical swimming to get high into the water column and eat phytoplankton while some carry egg yolks like a sack lunch.

Let’s go deeper

Unfortunately, most of what we know about larvae and their strategies come from shallow water systems. In deep-sea marine habitats, we lack both direct measures of how connected the network of individuals in a deep-sea species is, nor have we observed species’ particular dispersal strategy or how effective it is. One trait we have observed in deep-sea larvae is vertical swimming, whereby larvae actively swim to the surface to catch stronger currents that act as a turbo boost spreading larvae across the ocean. Dr. Stefan Gary and colleagues wanted to quantify just how much this vertical swimming behavior helps them disperse in deep sea habitats.

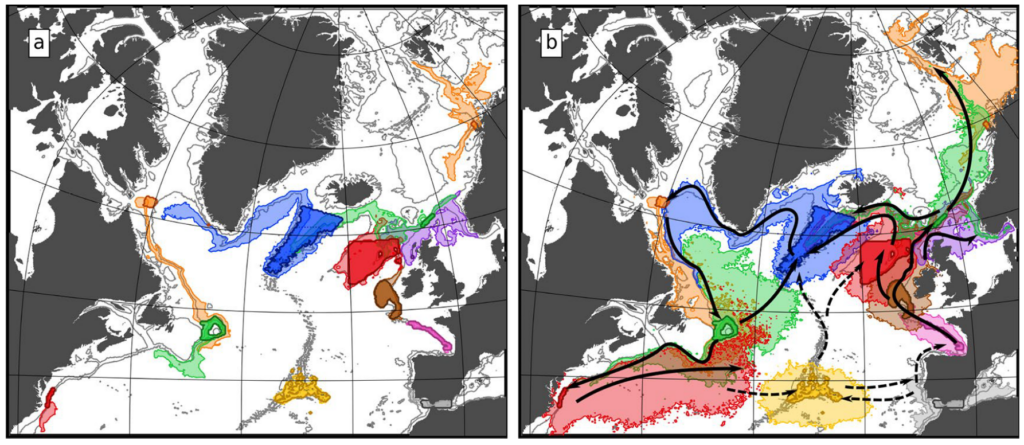

They modeled 200 dispersal events across 12 sites in the North Atlantic by mimicking larval release and using oceanic data – currents, tides, water temperature – to map where the larvae could go and how far they could travel. Larvae are plankton, meaning they cannot overcome the force of the currents. So, they can be modeled like particles with random motion on the small-scale but forced by environmental conditions on a large scale. To get an idea of what this kind of model would look like, check out this youtube video below from a different geographic location.

Because we know so little about deep-sea larvae, the scientists only tested the effect of vertical swimming behavior and left all other larval behavior or conditions that might influence dispersal constant in their model. Five attributes of vertical swimming were included that could influence the strength of the behavior: 1. the age at which larvae exhibit vertical swimming ability, 2. the age they begin to settle to the seafloor, 3. the maximum upward swimming speed, 4. the maximum downward swimming speed, and 5. the target depth above the seafloor that the larvae are swimming towards. The combination of these attributes created 32 uniquely modeled larval vertical swimming strategies.

To swim up or not to swim up

The work by Dr. Stefan Gary and fellow scientists shows that vertical swimming strategies used by larvae strongly influence how wide they are able to spread in the deep sea. They found that the widest dispersal was modeled by larval strategies that maximize time near the water surface while the lowest spreading was modeled by larval strategies that limit upward swimming and try to stay at the seafloor. The unique dispersal strategies led to different potential areas available for settlement and illustrated how much vertical swimming could influence the connectivity of deep-sea benthic species. The widest dispersing strategy modeled shows deep-sea larvae are likely able to access the entire North Atlantic ocean basin while the least dispersive modeled strategy suggest deep-sea larvae are retained mostly near the adults.

These different spatial configurations show species can have very different ranges, degrees of connectivity, and would require different management to encompass the area the animals use. Before we can apply their results to management and conservation efforts in the deep-sea, much more data is needed about the benthic deep-sea communities. The authors remind us that vertical swimming of larvae modeled in this study is only one of many tools larvae use to disperse. The influence of other attributes used by deep-sea larvae are currently unknown nor do we know which larval strategies are utilized by given deep-sea animals.

I am a PhD candidate in Biological Oceanography at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. I use DNA found in the environment (eDNA), like a forensic scientist, to detect deep-sea animals and where they live. When I am not studying the ocean, I am most likely in the ocean surfing or diving along the beautiful coasts of O‘ahu.