Duarte, C.M., Agusti, S., Barbier, E. et al. Rebuilding marine life. Nature 580, 39–51 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2146-7

Flooded coastal cities, sea turtles choking on plastic, dying coral reefs… these are the scenes we often picture when we envision the future ocean. Yet a team of the world’s leading marine scientists reports that we are capable of reversing this narrative in thirty years—if we are up to the challenge.

Our planet is a blue planet. The ocean is vital to our existence: It shapes our weather and climate patterns, provides over half of the oxygen in every breath we take, and is a source of food, minerals, and medicine. As the climate crisis escalates, we are increasingly looking to the ocean for sources of clean energy and ways to combat climate change. However, our one-sided dependence has wreaked havoc on many marine species and natural areas. In the last four decades, marine life has declined by nearly 50%. We must change course, or risk losing this blue planet we call home.

Return of the Humpback Whales

While waves of pessimism dominate news about the ocean, marine conservation success stories do exist. Take the case of the humpback whales.

In colonial Australia, whaling was a booming business. It employed thousands of men and generated export products worth millions of dollars. By the mid-1900s, the humpback whale population had collapsed and the species were labelled as endangered. As these giants of the deep teetered on the brink of extinction, a global anti-whaling movement began which culminated in a moratorium on commercial whaling in 1982. Over the next decades, humpbacks slowly rebounded. Today, they number in the tens of thousands—and were recently taken off the endangered species list.

The return of the humpback whales is a prime example of how multiple countries can band together to solve a seemingly unsurmountable problem. In a recent report for Nature, an international team of scientists led by Carlos Duarte documented the recovery of marine populations and their homes following past conservation efforts, demonstrating that marine life is resilient—and that if we take specific actions now, we can substantially rebuild marine life by 2050.

Under Pressure

The scientists began by reviewing initiatives to stop ocean degradation and assessing their successes to date. Historically, the main human pressures on marine life have been hunting, fishing, deforestation, and habitat loss. More recent threats are pollution, which became a widespread problem with the large-scale production of fertilizers, chemicals, and plastics in the 1950s, and climate change, which is caused by greenhouse gas emissions that have accumulated in our atmosphere since the industrial revolution.

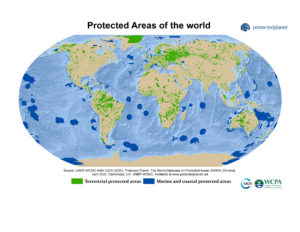

In the latter half of the 20th century, countries and international organizations began to implement initiatives to limit human impacts on the ocean. The MARPOL Convention was adopted in 1973 to prevent pollution from ships, such as sewage, oil, and garbage. Since then, large oil spills from oil tankers have declined by 14-fold. To safeguard ocean habitats, countries have established Marine Protected Areas, which are swaths of ocean in which human exploitation is restricted or banned. In 2000, less than 1% of the ocean was protected; today, MPAs cover over 5% of the ocean area.

Roadmap to Recovery

After thoroughly studying past ocean conservation interventions and recovery trends, the team developed a roadmap for rebuilding marine life. They identified nine components that are crucial for a healthy ocean. Seven of these—coral reefs, salt marshes, mangroves, seagrass meadows, kelp forests, oyster reefs, and the deep sea—are habitats that play a central role in sustaining ocean life. The other key components are fisheries, which are a vital source of food and livelihoods, and megafauna, or giant sea creatures.

In order to restore these key habitats and species, the team defined six “recovery wedges”: Protecting species, harvesting wisely, protecting spaces, restoring habitats, reducing pollution, and mitigating climate change. Within each wedge, they specified protective actions based on each habitat. For example, to restore coral reefs, we must reduce excess sediment and nutrient inputs and rebuild food webs.

The Climate Problem

One major roadblock stands in the way of rebuilding marine life: climate change. Over the last 200 years, the ocean has quietly absorbed one-third of the carbon dioxide released by humans. As the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide, its waters become more acidic, making it more inhospitable to ocean life. While nations across the globe are committed to fighting climate change through the Paris Agreement, few are on track to meet its temperature targets. At present, we are marching toward a warming of 2.6 to 4.5oC by the year 2100.

[box]The Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement is an international pact to limit global warming to well below 2oC above preindustrial levels, and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5oC, by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. While these temperature increases seem small, they have devastating impacts—heatwaves, droughts, flooding, loss of biodiversity, and increased disease, to name a few. Since the negotiation of the agreement in 2015, every nation on earth has signed (yes, even North Korea). This may change, however, given the Trump administration’s plans to withdraw the United States from the agreement. [/box]

From Whaling to Whale-Watching

Duarte and his team have handed us a playbook for rebuilding marine life. To run its plays, governments, businesses, and societies must join forces. This will require financial support of at least US$10-20 billion per year. But, the economic return will be vast—around US$10 per $1 invested. Rebuilding fisheries could boost the global seafood industry by US$53 billion. Conserving coastal wetlands, which reduce storm flooding, could save the insurance industry US$52 billion annually. Protecting ocean areas can boost ecotourism, a lucrative business that provides nearly 54,000 full-time jobs in the Great Barrier Reef alone. And over the course of its lifetime, one whale is estimated to contribute $2 million through industries such as whale-watching.

Source: Culture Trip

The Grand Challenge

Based on their findings, the marine experts conclude that although facing this “Grand Challenge” will not be easy, it is within our reach. Other leading scientists echo this sentiment. Speaking in an NPR podcast, Tom Rivett-Carnac, a political strategist who helped orchestrate the Paris Agreement, sums up why we should throw down the gauntlet:

“If you look at the components of this crisis, it is overwhelming odds; it is clock ticking down; it is great peril if we fail—it’s all the ingredients of a great adventure story…

To me, that’s the beginning of a really inspiring narrative. I want to be part of the generation that faced this challenge, decided it wasn’t too much for us. And then we’ll always be the generation that was able to do this. That’s still a chance for us.”

Rome wasn’t built in a day. The ocean, in fact, took millions of years to form. That we might rebuild marine life in mere decades—if we take decisive action now—is remarkable. What are we waiting for? ■

I am a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University where I am developing an underwater instrument to study the coastal ocean. I have a multi-disciplinary background in physics and oceanography (and some engineering), and my academic interests lie in using novel sensors and deployment platforms to study the ocean. Outside of my scholarly life, I enjoy keeping active through boxing and running and cycling around Boston.