Who doesn’t love seafood? Because of seafood’s popularity, especially during these warm summer months in coastal communities, there’s been a drastic rise in the amount of pressure put on certain fisheries. Salmon, tuna, and shrimp, for example, are some of the most loved seafood – but also some of the most unsustainable fisheries due to exorbitant demand. As a lover of seafood and the environment, it can be tough to find a sustainable fix for those fishy cravings.

Recently, conservationists have been recommending trying “something new” to take pressure off popular fisheries. More evenly spread demand for different seafood gives wild populations a bit of a break while reducing the need for unsustainable fish farms. This “something new” could just be the extravagant, highly venomous, and incredibly invasive lionfish.

An invasive species is one that’s been introduced by humans (either purposefully or by accident) into an environment outside their natural range. Invasive species harm their new environments because they lack natural predators and their prey don’t know they exist. Red and common lionfish were first spotted in Northwestern Atlantic waters around 1985, most likely because humans released their unwanted pet lionfish into the wild. By 2001, these lionfish were considered an established species in the Northwestern Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico. Lionfish easily cause immense damage. They eat absolutely everything- studies have actually found the presence of over 50 families of fish and invertebrates in lionfish diets. Also notable are their rapid breeding rates; a female lays about 2 million eggs every year. Paired with an overall absence of natural predators, the lionfish has easily become a top predator in the Atlantic and other tropical waters. Unfortunately, researchers have agreed that we can’t naturally abate the damage of this species – and that’s where we come in.

A great way to deal with an invasive species with no natural predators is to eat it ourselves. Because lionfish are venomous, not poisonous, their flesh poses no threat to humans when ingested. In order for venom to take effect, it needs to be injected, not ingested. All we have to do is cut off their venomous spines, and we’re left with a seafood choice that has a consistency of anywhere between whitefish and chicken nuggets. Eating lionfish takes an invasive species out of the Atlantic equation. Better yet, most lionfish are sourced through spear fishing, a method with minimal chance of bycatch. The Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch app and website lists lionfish as a “Best Choice” seafood– one of the most sustainable choices available. Grocery chain Whole Foods has also made a commitment to selling lionfish in an effort to promote sustainable fisheries. Overall, lionfish are taking off both in population numbers but also in its potential as a delicious, eco-friendly seafood.

One of the major obstacles in establishing lionfish as a new, sustainable fishery is the common problem that most top level predator fisheries face: the bioaccumulation and biomagnification of heavy metals or toxins (for more on these topics, read here and here). Specifically, because of their new, established presence in the tropical and subtropical Northwestern Atlantic, lionfish can be the prime vectors for biomagnified levels of ciguatoxins. Ciguatoxins are produced by the microalgae Gambierdiscus which grows in and around coral reefs in tropical and subtropical environments, exactly where these invasive lionfish have settled. When ingested by consuming seafood, ciguatoxins can cause ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP) in humans characterized by diarrhea, vomiting, sensitivity to temperature, dizziness, and cardiovascular and neurological symptoms. CFP is one of the most prevalent non-bacterial illnesses associated with fish consumption with about 50,000 cases reported annually. Similar apex predators in the Northwest Atlantic like barracuda, grouper, and snapper can be highly ciguatoxic, and previous studies have established that lionfish can also biomagnify ciguatoxins and put their human consumers at risk of CFP. Before we can establish lionfish as a viable, healthy, and eco-friendly commercial fishery, we need to understand what their current concentrations of ciguatoxins are.

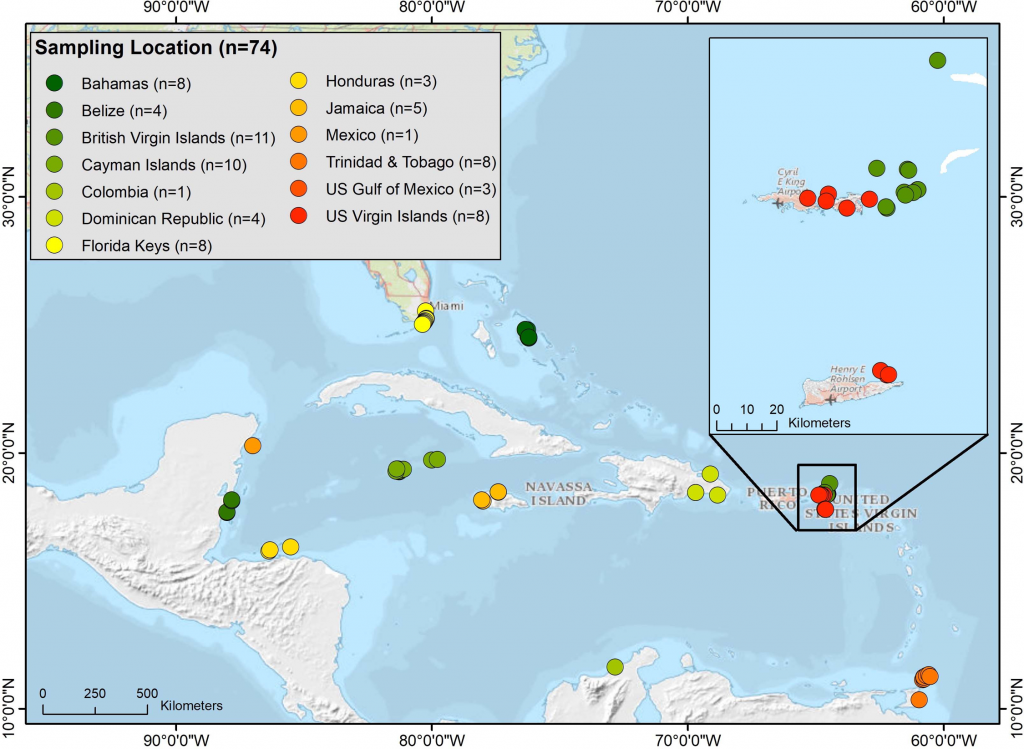

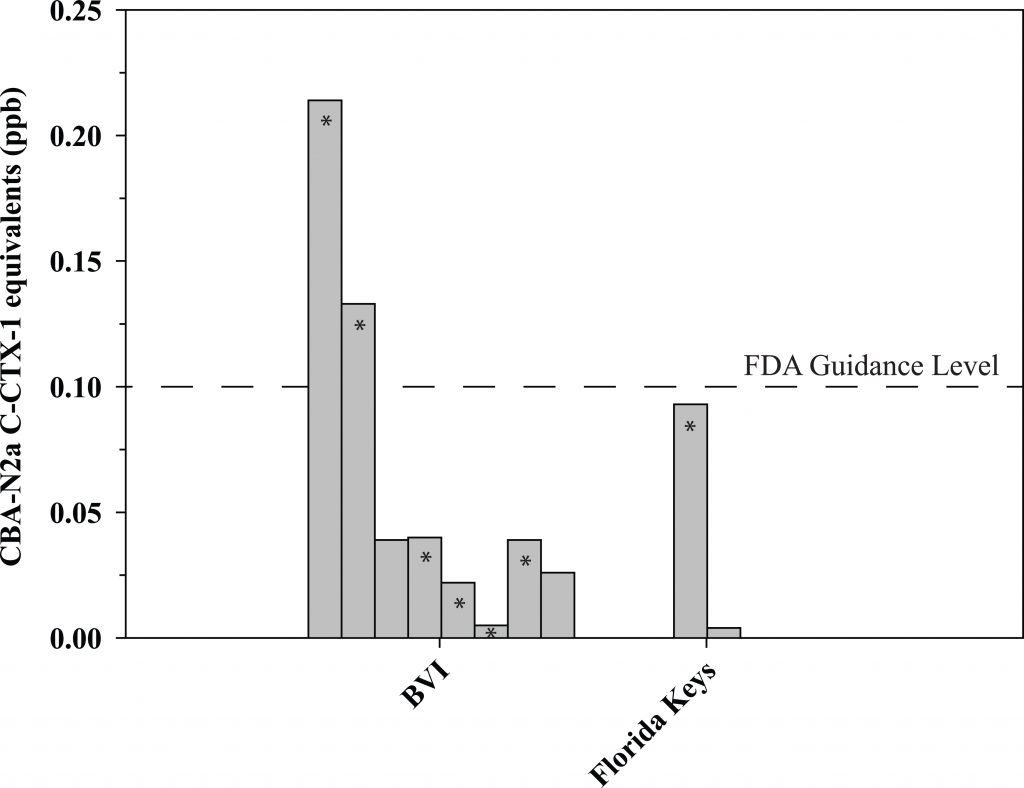

Hardison et al. (2018) examined 293 lionfish samples all around the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico for a total of 74 sampling sites. They conducted two separate tests to detect ciguatoxin concentrations and found that just 30 lionfish exhibited some concentrations of ciguatoxins, but only 2 lionfish held concentrations above the FDA guidance level. Interestingly enough, these two lionfish were sourced from the British Virgin Islands, a “hot spot” known for its high CFP rates. Results indicate that lionfish, just like other top level predators, biomagnify ciguatoxins in these hot spot areas. Through these results, we can understand that the best path forward to support and concretize lionfish as a new, viable commercial industry is to rely on prior knowledge about ciguatoxin concentrations in top level predators of the area. Additionally, just as these predators biomagnify ciguatoxins through their carnivorous diet, we too can biomagnify ciguatoxins over time; even eating fish with low levels of ciguatoxins can eventually result in CFP.

While there’s much more work to be done in terms of assessing the fish prone to high concentrations of ciguatoxins, lionfish from the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico had very low instances of ciguatoxin concentrations. When they did, it generally was below the FDA guidance level. For the adventurous, lionfish still remains an excellent choice. In addition to enjoying a guilt-free, new seafood option, scientists recommend supporting additional monitoring programs to survey ciguatoxin concentrations in not just lionfish, but other commercially viable fish around the Northwest Atlantic.

Rishya is a multimedia science communicator with an MS in Media Advocacy from Northeastern University, specializing in Environmental Science Communications and Policy. She spent a year in informal education and policy advocacy at the New England Aquarium as an Educator and at Save the Harbor/Save the Bay as their Communications and Public Relations Coordinator. She also interned for PBS science series, NOVA and was awarded a 2019 Rapport Public Policy Fellowship, which she served at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. Rishya’s areas of focus are environmental science, marine science, climate change…and video games!